In ancient Rome, especially during the Republic, it was of great importance to show the fame and greatness of one’s ancestors, which served to strengthen the family’s standing in society, and serve as a prompt to its younger members that they must strive for a similar renown. One way of expressing the distinguished ancestral line of a family was the display of imagines, death masks as famously described by the Greek historian Polybius. These were the funeral masks of ancestors that were displayed in the atriums (entrance hallways) of aristocratic houses, that were designed to impress visitors, and provide a reminder to the family lineage.

The Romans celebrated the accomplishments of famous men and some women with statues made of marble, dedications on grand buildings and temples, and majestic tombs (think the Scipio family here). One rather obscure artefact, mostly forgotten because of the lack of archaelogical evidence, are the death masks, or as they are known in Latin, imagines. Made of wax, these imagines were a remarkable likeness of the person.

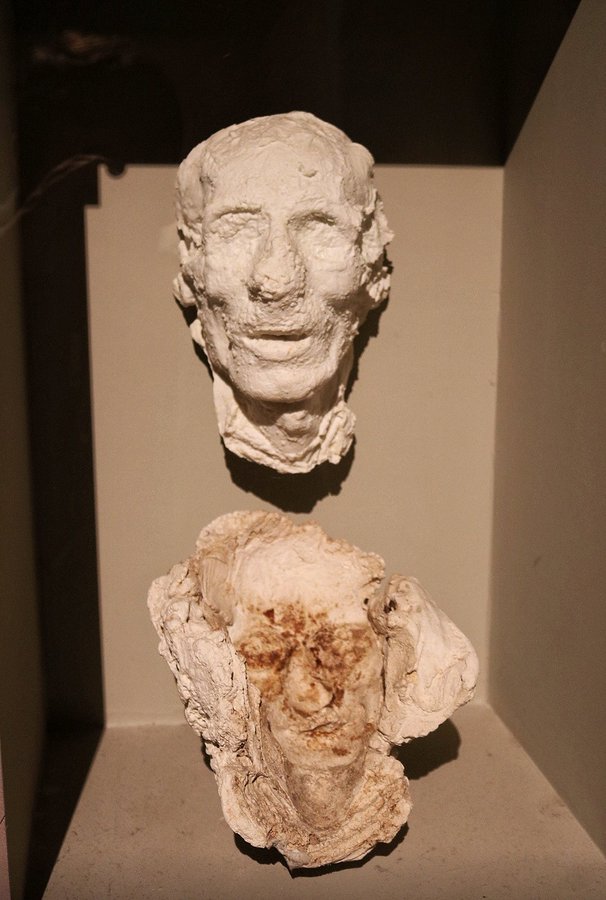

CE. Exhibited along with a silicone cast taken from it. Archaeological Museum of

Thessaloniki

They were a way of remembering the dead family member, and were displayed at public funerals, often worn by actors, serving as a link between the dead and the living.

Both Pliny the Elder and Polybius tell us how the masks were made. Some scholars, sponsored by the Penn Museum in Philadelphia sought to recreate these imagines (see the link below). They discovered that they were not created following the death of the person, but during his lifetime, most likely between the ages of thirty-five and forty, when a man had attained physical maturity and political office.

Polybius tells us of the funeral of an “illustrious man”:

“Whenever [an] illustrious man dies, in the course of his funeral, the body with all its paraphernalia is carried into the forum to the Rostra, as a raised platform there is called, and sometimes is propped upright upon it so as to be conspicuous, or, more rarely, is laid upon it. [A] likeness consists of a mask made to represent the deceased with extraordinary fidelity both in shape and colour. These likenesses they display at public sacrifices adorned with much care. And when any illustrious member of the family dies, they carry these masks to the funeral, putting them on men whom they thought as like the originals as possible in height and other personal peculiarities.”

Observing the row of accomplished ancestors being portrayed by actors, Polybius goes on to say, “There could not easily be a more ennobling spectacle for a young man who aspires to fame and virtue. For who would not be inspired by the sight of the images of men renowned for their excellence, all together and as if alive and breathing?”

The actors brought the ancestors back to life, and their achievements endured after death. The practice was instrumental in inspiring him to earn his place among them by his own exploits, be they political or military, and to be remembered alongside his illustrious forebears.

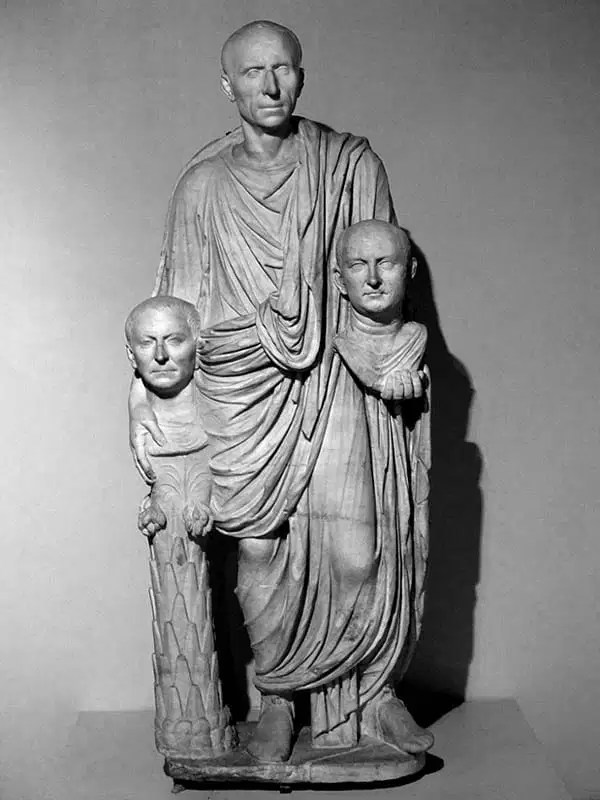

Togatus Barberini, Roman marble sculpture from the first-century AD, depicting a figure holding the heads of deceased ancestors in either hand. Housed in the Centrale Montemartini in Rome. Thought to be a representation of the Roman practice of creating death masks with which to honour the dead.

The Romans led by example, and the constant reminder in the home of the achievements of one’s ancestors would spur a young man on to try and achieve the same. The possibility of death would not deter him, because the memory of what he managed to achieve would live on. This pragmatism pervaded and served Roman society at almost all levels.

Because of their fragile nature, no imagines have survived. No literature, ancient history, or artwork tell us how they were made. The scholar Valerie M. Hope supposes the “possibility that these masks may also have played a role in the funeral ritual” (Roman Death: The Dying and the Dead in Ancient Rome), which is a distinct possibility when looking at the image below:

Although this unfortunate child’s mask was made inadvertantly, it shows how such masks became entwined with the funeral practices in ancient societies. Like the Greeks, the Romans believed in the soul and had a belief in the afterlife, therefore remembering the dead, either collectively or individually, was a duty of some sorts. The funerals of the elite were certainly well-crafted and stage managed affairs, and because these events were remembered by the citizens attending, hence the dead were being remembered, as if through their achievements and renown, they were still living. At Caesars funeral a wax effigy of the man was displayed complete with stab wounds and fake blood.

Click here for an article on how the Romans made their funeral masks and here for an interesting downloadable article called Breaking the Mould, about Roman plaster death masks, then you can watch the video below showing a re-enactment of a somewhat bizarre Roman funeral.

References:

Histories. Polybius. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. translator. London, New York. Macmillan. 1889. Reprint Bloomington 1962.

Leave a reply to Verism: Portraying Power and Ancestry Cancel reply