It was the year 155 BC that philosophy arrived in Rome, when a delegation of three Greek philosophers, Diogenes, Critolaus and Carneades arrived on a political mission, to negotiate the settlement of war fines payable by Athens for pillaging the city of Oropos. During their stay they succeeded in raising Greek philosophy to the Roman publics attention and laying the groundworks for its future role in Rome.

Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, which were first given credence by Diogenes the Cynic in Corinth, Stoicism laid great emphasis on the goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature. Proving very popular, (the Romans were especially impressed by Diogenes), it flourished as one of the major schools of philosophy in the Roman era, amongst all levels of society. Stoicisms’ understanding that all humans are linked, and nature is the one true divine, fitted nicely in with the Roman Imperial idea of conquest and control.

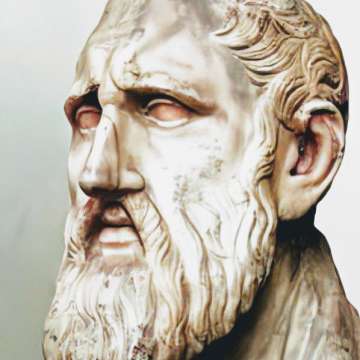

Stoicism, initially taught by Zeno (above) in Athens, had many adherents among the Roman elite, including Pliny the Elder, Cicero, Virgil, Cato and Seneca the Younger, and the Emperor Marcus Aurelias (although not Cato the Elder it has to be said, who thought the visiting Greek philosophers to Rome were trying to corrupt the Roman youth), who saw the traditional collection of Roman Gods as nothing more than figureheads to keep society stable, and the lower classes feeling secure in their station in life. They as Stoics, looked beyond the traditional pantheon of gods, and viewed nature as the true creator of all on earth, and one who should be respected. But still, the presence of the gods was an integral part of life in the Roman state, and the state built temples to the gods and observed rituals and festivals to honour and celebrate them. This was daily life in the Roman Republic and later, the Empire. Nonetheless, most Roman citizens largely saw the gods as caring little about the morality of the people, and only concerned was being paid tribute through rituals.

Stoicism gradually gained widespread support among all classes of Roman society. It had just one overwhelming and highly practical ambition: to teach the people how to be calm and brave in the face of adversity in their lives. It was your choice whether to live in accordance with the divine plan, or to fight against it, for the sake of material goals. The philosophy would say it is wise to never believe in the gifts of Fortune: money, fame, love, power – these are never our own, they are given to us by the Gods, sometimes fleetingly. They are never truly ours, so we must strive not to be owned by them. Enjoy them but never forget they can be taken away in a single day. And to never forget others who have lost them, or never had them in the first place.

In truth, the Stoics seldom followed the philosophers of Greece in their attitude towards money and comfort, many of them being wealthy men, but they did share their their ability to try and maintain perspective in times of crisis, to keep ones equilibrium in an uncertain world. Theirs was often the case of, do as I say, not as I do. Seneca, despite being lauded for his written works on clemency, abstinence, and mutual kindness, died a very rich man. Pliny said of him, [he was] ‘the foremost of intellectuals, whose power ultimately overcame him’, records Daisy Dunn in her excellent book In the Shadow of Vesuvius, 2019. Although Stoicism was supposed to be an improvement of the self, and therefore it was discouraged to talk about one’s philosophy, several of them were vocal and were sometimes accused of being sanctimonius about their views.

Stoicism encouraged a respect and reverance towards nature. Pliny the Elder, author of the extant encyclopedia Naturalis Historia (Natural History) completed in AD 77, the largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire, ‘objected to mining of the Earth on both environmental and moral grounds, saying probing the bowels of the earth for gold and silver, amber, bronze, iron and gems, ”as if the ground we tread were not generous or fertlie enough” was wrong’ (Dunn, 2019). He went further saying; ‘Man would do well to understand that, while the sweeping of oceans and ploughing of rich landscapes is ruinous to the earth, it is positively deadly to his own true interests’ (Dunn, 2019).

Their philosophy taught the Stoics that it was foolish to prolong life just for the sake of enduring pain, but cowardly to seek death because of pain alone. Seneca had declared that “Life without the courage for death is slavery”, Pliny’s friend Euphrates, committed suicide to escape the pains of illness and old age, which Roman society deemed a perfectly acceptable course of action. Cato the Younger is said to have died a death totally consistent with Stoic philosophy, when having retired to a cave in North Africa after his defeat at the Battle of Thapsus, he read and re-read Plato’s Phaedo, before disembowelling himself with his sword and bleeding to death. Cato wasn’t displaying a contempt for life, but rather life had no more importance, so it was acceptable to end it.

‘But for that briefest of moments when we feel pleasure, innumerable fish courses are prepared, the sea is sailed to it’s furthest limits; cooks are far more sought after than farmers; some prioritise their meals over spending on their estates, though our bodies are in no way aided by extravagant food ‘ – Musonius Rufus AD 30 – 101

Musonius Rufus was known as the Roman Socrates, taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero, and was sent into exile in 65 AD when the Emperor thought he was involved in a plot on his life, returning only after his death. During the civil war that erupted after Nero had been forced to commit suicide, Rufus was sent as an envoy to negotiate a peace agreement with the opposing side, but ended up debating the horrors of armed conflict so much, he was ridiculed for his ‘untimely wisdom’ (Dunn, 2019). He was one of the very few Romans to argue for women’s equal treatment saying ‘because men’s and women’s capacity to understand virtue is the same, both should be trained in philosophy’ (Diotima, 2014). Rufus was known to be admired by many including the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and his observation ‘What good are gilded rooms or precious stones, fitted on the floor…carried from great distances at the greatest expense? These things are pointless and unnecessary…Don’t they cost vast sums of money that, through public and private charity, may have benefited many?’, is thought to have influenced Aurelius, helping him to decide to sell his family jewels to raise money for the state after it struggled financially during the Germanic wars. He was one of the five good Emperors, (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonnius Pius, and Aurelius who ruled over a period of peace and prosperity known as the Pax Romana, between 96 – 180 AD), cancelling 45 years worth of debt to the Roman people, embarking on a building programme including the construction of baths, temples, aqueducts, amphitheaters, and roads.

The Stoics believed that enthusiasm was wisdom of the soul, they had, or tried to nurture, patience and the capacity to tolerate and accept their circumstances. They had the mindset that any positive attitudes they had were further enhanced when supported by a wholesome spiritual wisdom that strengthened their ability to endure.

Perhaps in our modern world, we can learn a thing or two about how to live, from these people. Recently, during the pandemic, life has been extremely difficult for many people, and lot of us now know about death, having experienced it at first hand, probably for the first time in their lives. Now as the cost of living crisis bites, and the wars in the world seem more aggressive than ever before, life keeps throwing obstacles in our path when all we want is a peaceful existence. We have been through hard times before, and there’s no doubt we will again. The trials of life keep moving us forward if we choose to swim with the flow, and slow us down if we struggle against it. For many of us, it seems that struggle is a constant part, often the gretater part of life, so perhaps we should embrace it rather than fight it. Do we need to adopt the attitude that we should seek out challenges, or rather we should wherever possible, avoid them. The basic philosophy of Stoacism is that every tragedy should have already been thought of, rationalised and prepared for. If it doesn’t happen then that’s a bonus.

Understanding these things before they happen should help to make us both suspicious of success and accepting of failure. In every sense, much of what we get, we don’t deserve. In these strange times that we are living through, we need to be stoical in the face of what happens to us in relation to our jobs, our income and of course our health, both ours and our loved ones.

This is a good time to find a talent laying dormant inside us, something that will help someone to get through their own difficult period. In every crisis in our lives comes an opportunity to see things from a different perspective, or to do things differently. Human beings, to a degree, seem to enjoy adversity, they thrive on a challenge. It brings out the best in some of them.

Many famous actors and musicians say the happiest time of their careers were when they were playing every role they could get their hands on, or every gig they could, just to practice their craft and find their audience. Once fame arrived, the luxury to choose and command a large fee stripped away a lot of the enjoyment from what they were doing.

By pushing ourselves, and stepping outside of our comfort zone we often grow. We sometimes discover talents we never knew we had, or delight in doing new things, realising the things we were forced to leave behind had no real meaning for us.

For a downloadable copy of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations click here

References:

Daisy Dunn, In the Shadow of Vesuvius, copyright 2019, published by William Collins, 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

Diotima, Philosophers on the Role of Women, archived 2014 at the Wayback Machine (The Wayback Machine is a digital archive of the World Wide Web founded by the Internet Archive).

Leave a comment