Unknown Artist, c.1800, National Trust for Scotland, Brodick Castle, Garden & Country Park

Andromeda was the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, Cepheus being the King of the Ethiopians. When Cassiopeia boasted of her beauty being greater than that of the Nereids (the 50 daughters of the ‘Old Man of the Sea’ Nereus and the Oceanid Doris, sisters to their brother Nerites), they complained to Poseidon who was so enraged by the queens arrogance he sent a flood and a sea monster to destroy the kingdom. The surest way to incur divine wrath it seems, was to boast of having some kind of wonderous quality such as beauty or skill.

An oracle predicted that deliverance would only be given if the beautiful daughter of the royal couple were to be sacrificed to the sea monster, so Cepheus reluctantly chained Andromeda to the cliffs by the sea to await her fate.

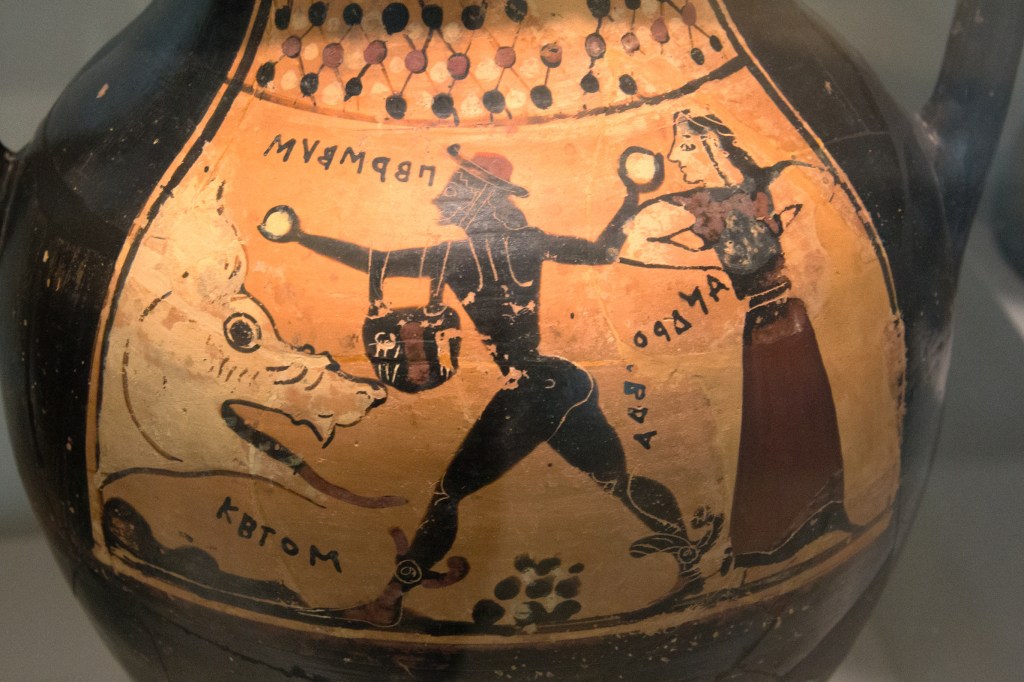

Here enters Perseus who spotting Andromeda, awestruck by her beauty, agrees to rescue her if she will marry him, to which she, and her parents willingly agree. Perseus duly dispatches the sea-monster and takes Andromeda as his bride. The kingdom is saved.

The site of Andromeda’s rescue was said to be at Joppa, where marks on the rocks by the shoreline that were said to have been made by the chains that bound her, were still being pointed out in the first century AD. Near Joppa was a well that ran with red water, said to be where Persues washed the blood from his hands after slaying the sea-monster.

But it is that Perseus was a white Greek hero, and Andromeda a black woman from the Kingdom of Ethiopia that is interesting. Andromeda has, since Ovid’s retelling of the already centuries old myth nearly two-thousand years ago, has usually been portrayed as white. Ethiopian in Greek meant ‘burnt faced’, and Ovid often refers to the beauty of this dark skinned woman. Yet in almost every telling of the myth, and it’s associated paintings and sculptures show Andromeda as a white european.

The classical stories are clear on one thing, Andromeda was a Princess of Ethiopia. It is important here to understand the ancient world did not have the same concepts of race, and racial division as we sometimes do today, and that ancient Ethiopia does not necessarily have the same geographical boundaries as the North African country we know now.

In the ancient world Ethiopia was both a ‘legend that has both Asiatic and African origins.’ The Greek sources vary on giving an exact physical description of her beauty, only agreeing that it was overwhelming, it certainly grabbed Perseus’s attention. A clear picture of her appearance is drawn by Ovid, who describes her as having dark skin and beautiful. He describes her as ‘fusca’, meaning black or brown, and in his Ars Amatoria, he writes that Andromeda was carried by Perseus from ‘Black Indians’, and when advising women on what to wear, he says that women with dark skin should wear white clothes, as Andromeda did, to enhance their beauty.

Ovid has Perseus describing Andromeda as a “marble statue.” Some people have thought that this means she was white, but Ovid is merely making the point that she looks like a beautiful statue, and in Roman times marble statues were painted with vibrant, sometimes gaudy colours. Over the centuries that paint has eroded and faded away, leaving us with a pure white statue. This, since the renaissance, has connected pure whiteness to the Classical ideal of Rome and beauty. We also need to remember, marble comes in a variety of different colours, and one of them is black.

The myth of Andromeda was of Greek origin, but it was the Romans who were well-versed in appropriating what they wanted from foreign influences, including myths and religions, and absorbing them into their own culture. When Ovid wrote his Metamorphoses his ‘stated ambition was to create a “new form” of literature by focusing on how ‘bodies changed into new forms’.

In the sculpture at the top of this page, held by the National Trust for Scotland in Brodick Castle, Andromeda, although sculpted in black marble, has distinctly european features, but the British born artist of Ghanaian, Anglo-Jewish and Jamaican family heritage Kimathi Donkor, painted The Rescue of Andromeda in 2011 introducing a new take on the myth. Andromeda herself is of African heritage and Perseus is nowhere to be seen. The monster has been relegated to a dark background, and Andromeda certainly is not in a scared and helpless position, rather she looks quietly confident and composed. A strong woman, not a victim, in a stand and fight stance rather than ready to flee. Donkor’s work is perhaps in some way giving back to Andromeda that which has been lost over the centuries.

Sources: Andromeda and the Erasure of Black Beauty, Kimathi Donker, The Rescue of Andromeda, & Emma Bridges in the Introduction of Introducing Greek and Roman Myth, Block 1 for the Open University 2022.

Leave a comment