The following article was published in The

Guardian online by Harriet Sherwood on

Thursday 17th April 2025

The pivotal ‘barbarian conspiracy’ of AD 367 saw Picts, Scotti and Saxons

inflicting crushing blows on Roman defences. A series of exceptionally dry

summers that caused famine and social breakdown were behind one of the

most severe threats to Roman rule of Britain, according to new academic

research.

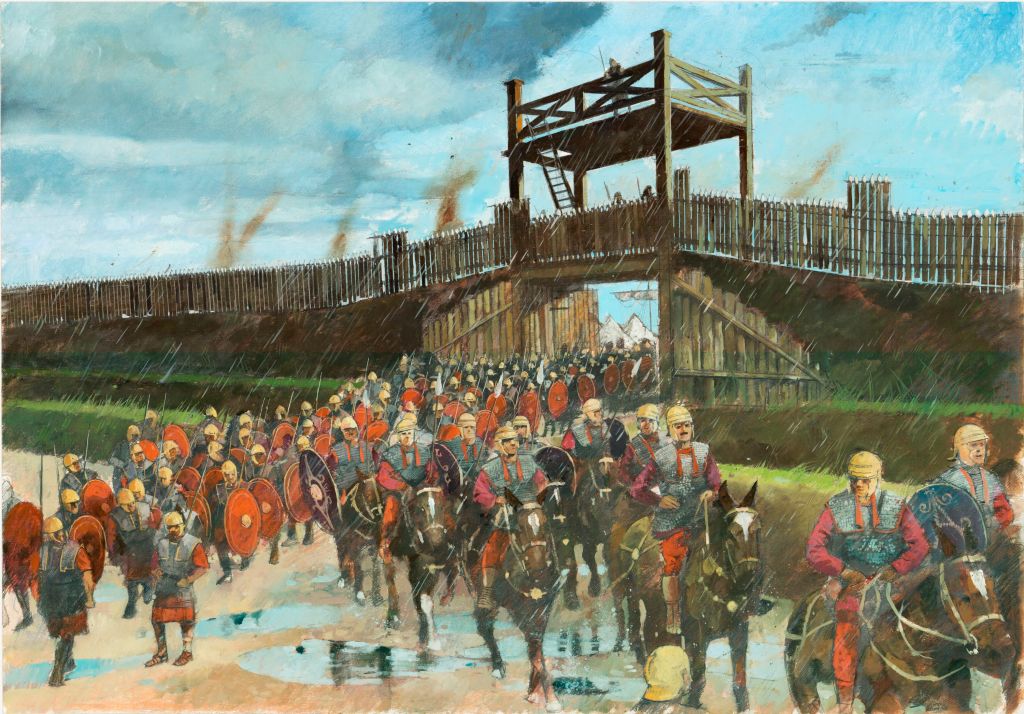

The rebellion, known as the “barbarian conspiracy”, was a pivotal moment

in Roman Britain. Picts, Scotti and Saxons took advantage of Britain’s descent

into anarchy to inflict crushing blows on weakened Roman defences in the

spring and summer of AD367.

Senior Roman commanders were captured or killed, and some soldiers

reportedly deserted and joined the invaders. It took two years for generals

dispatched by Valentinian I, Emperor of the western half of the Roman Empire,

to restore order. The last remnants of official Roman administration left Britain

about 40 years later.

Warning of the possible consequences of drought today, Tatiana Bebchuk, a

researcher at Cambridge’s department of geography, said: “The relationship

between climate and conflict is becoming increasingly clear in our own time,

so these findings aren’t just important for historians. Extreme climate

conditions lead to hunger, which can lead to societal challenges, which

eventually lead to outright conflict.”

The study, published in Climatic Change, used oak tree-ring records to

reconstruct temperature and precipitation levels in southern Britain during

and after the barbarian conspiracy. Combined with surviving Roman

accounts, the data led the authors to conclude that severe summer droughts

were a driving force.

Little archaeological evidence for the rebellion existed, and written accounts

from the period were limited, said Charles Norman of Cambridge’s department

of geography. “But our findings provide an explanation for the catalyst of this

major event.”

Southern Britain experienced an exceptional sequence of remarkably dry

summers from AD364 to 366, the researchers found. In the period AD 350-

500, average monthly reconstructed rainfall in the main growing season was

51mm. But in AD 364, it fell to 29mm. AD 365 was even worse with 28mm,

and the rainfall the following year was still below average at 37mm.

Prof Ulf Büntgen of Cambridge’s department of geography said: “Three

consecutive droughts would have had a devastating impact on the

productivity of Roman Britain’s most important agricultural region. As Roman

writers tell us, this resulted in food shortages with all of the destabilising

societal effects this brings.”

The researchers identified no other major droughts in southern Britain in the

period AD 350-500 and found that other parts of north-west Europe escaped

these conditions.

By AD 367, the population of Britain was in the “utmost conditions of famine”,

according to Ammianus Marcellinus, a soldier and historian.

Norman said the poor harvests would have “reduced the grain supply to

Hadrian’s Wall, providing a plausible motive for the rebellion there, which

allowed the Picts into northern Britain”.

The study suggested that grain deficits may have contributed to other

desertions in this period, and therefore a general weakening of the Roman

army in Britain.

Military and societal breakdown provided an ideal opportunity

for peripheral tribes, including the Picts, Scotti and Saxons, to invade the

province.

Andreas Rzepecki, from the Rhineland-Palatinate General Directorate for

Cultural Heritage in Trier, said: “The prolonged and extreme drought seems to

have occurred during a particularly poor period for Roman Britain, in which

food and military resources were being stripped for the Rhine frontier.

“These factors limited resilience, and meant a drought-induced, partial-

military rebellion and subsequent external invasion were able to overwhelm

the weakened defences.”

The researchers expanded their climate-conflict analysis to the entire Roman

empire for the period AD 350-476. They reconstructed the climate conditions

immediately before and after 106 [different] battles and found that a

statistically significant number of battles were fought following dry years.

Leave a comment