When Julius Caesar and his his legions had finished their conquest of Gaul, a million Gauls and Germans were dead, and a million more were enslaved. In his decade-long conquest of what is today France, Belguim, North-West Italy and a small part of the Rhineland, Caesar made himself to be one of the greatest military leaders the world had known. He was to go on and teach his great nephew Gaius Octavius, (then a fifteen year-old boy drafted to Caesar’s staff) the art of leadership in both politics and war. When Caesar returned fron Gaul victorious he became Dictator for life, and almost immediately the trouble began, with many dark mutterings about him wanting to become king, complete anathema to the Romans.

Octavian was born to a niece of Caesar, in the upper-class residential area of the Palatine in Rome and the great leader would probably have been relieved to have a male relative as he had no son of his own, and legitimate male bloodlines were of real importance in Roman politics. Octavian’s family was plebian in it’s origin, and they had no real money or social standing, but that didn’t prove too big an obstacle.

The historian Suetonius, a biographer of Augustus, said that he had come into possession of a bronze statue of the young Octavin with the name Thurinus etched into the base, indicating he came from the town of Thurii and was therefore from humble stock. Marc Antony once belittled Octavian, calling him ‘the Thurian’, with Octavian responding ‘I’m suprised that a former name should be thrown at me as an insult’. The truth is probably that his father had adopted this cognomen, after hunting down a small band of runaway slaves in the area of Thurii, in order to distinguish the Octavian clan from other families. The point here is, because entrenched family priviledge and social standing were so important in Roman politics, Octavians rise to power is all the more so remarkable.

When Caesar was assasinated on the Ides of March 44 BC, by a group of conspirators led by Marcus Junius Brutus, the ancestor of the Lucius Junius Brutus who overthrew the last king of Rome in 509 BC, the eighteen year-old Octavian, who had been sent overseas to improve his knowledge of the Greek language and literature (his tutor Appollodorus of Pergamum being selected by Caesar himself), received a letter from his mother telling him of his great-uncles death and to beware – he may be next on the assassins list. The young man immediately set out for home to find out what had really happened. With a few of Caesar’s loyal centurions, he made a rough crossing of the Adriatic at night in a small boat, landed on a deserted beach to the south of the garrison port of Brundisium and made discreet inquiries about the situation in Rome. Only now did he realise Caesar had adopted him as his son and heir, and had left him the bulk of his fortune. More importantly, in his Will dated 13th September 45 BC, he had bequeathed Octavian his name, Caesar.

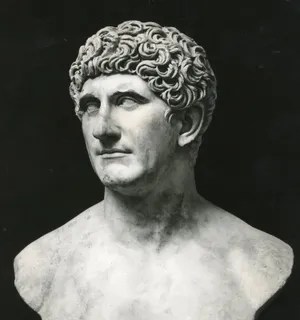

Meanwhile in Rome, Marc Antony, Caesars favourite general had taken command. Caesar and Antony had soldiered together in Gaul, and the dictator liked Antony vey much, but probably realised he was not best suited in temperment to high command, putting his trust in his young nephew instead, but keeping Antony in the dark about this. On Caesar’s death Antony saw an opening and grabbed his chance. He allied himself with another of Caesars generals, Lepidus, who controlled around 5,000 soldiers in Rome, and filled the forum with them, effectively surrounding the assassins. Antony however counselled caution, and chose not to arrest the conspirators, a big mistake in Octavian’s, and the public’s eyes. Many soldiers of the Roman army and almost all lower-class citizens viewed Caesar as a hero, and someone who was treacherously murdered.

Several of the assassins had already fled from Rome, the rest remained holed-up in safe houses on the Palatine, ‘prisoners of their own homes’ as Cicero called them. Antony had persuaded Calpurnia, Caesar’s widow, to hand him the money Caesar kept at home (quite a tidy sum in gold coin), along with his private papers. He also refused to allow anyone else to read the contents of Caesar’s Will, after seizing it from the treasury where the Vestal Virgins had been guarding it.

Antony was now in charge in a material sense, but he had yet to convince the Senate that he was the rightful heir to Caesar, as many politicians were uneasy with what was happening, and Antony was known to be something of a ‘loose cannon’. Already rumours were heard that Caesar’s son was making his way to the city.

At this time Octavian formed two friendships that were to prove both prominent and powerful in his life, one for good reasons, the other for bad. Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Salvidienus Rufus were from humble backgrounds and Octavian would rely on them heavily during the coming struggle. He had also secured the allegiance of Caesars legions in Macedonia, who had met him before he crossed to Italy. He would need them in the dangerous months ahead.

He sent his soldiers ahead of him to look for traps when he landed at Brundisium. They quickly came into contact with the garrisoned troops, and when they were told Caesars heir had arrived they marched out to meet him, calling him ‘Caesar!’ They also brought with them the news thay had in their control a huge sum of money Caesar had entrusted to them, ready for his Parthian campaign, which was due to commence in just a few days before he was assassinated. This was a huge moment for Ocatvian, he now realised just what lay before him, if he seized the opportunity.

Reaching Naples, Octavian was met by a man named Balbus, a Spaniard of Phoenician descent, who had managed the political and financial affairs of Caesar for many years. He was impressed by the young man and handed him a large sum of Caesars money that he had been taking care of. It was around this time that Octavian met Cicero, who wasn’t enamoured by the boy, saying ‘It’s just not possible that he can be a good citizen. He’s surrounded by…people who…can’t tolerate the present situation, and…menace our friends (the assassins) with death’. Cicero was not aware of the plot to kill Caesar, although he did later agree with it, later saying “All honest men killed Caesar…. some lacked design, some courage, some opportunity: none lacked the will.”

Octavian’s arrival in Rome was met with indifference by Marc Antony who kept him waiting for an interview for an improper length of time. In the meeting, Octavian politely demanded he be recognised as Caesars heir and asked Antony to release the dictators money and papers to him. Antony refused, saying he needed the money to pay the 300 sesterces Caesar had bequeathed every freeborn citizen living in Rome (for comparison, a craftsman or a legionnaire could earn around 900 sesterces a year), and of the papers and Will he refused.’

Octavian responded by selling large amounts of his family’s property in order to raise the money to fulfil Caesar’s last wishes. This, and a public campaign to introduce himself to the general public was starting to reap rewards. Octavian was already an accomplished orator, and his popularity soared, while Antony’s plummeted. The public did not like the way he had shown leniancy with the assassins whilst belittling Octavian. The general had also brought 6,000 troops into the city, an illegal act, and the Senate were aghast. When asked why, Antony replied ‘They are my personal bodyguard’. Everyone, including the public, were now wondering if although Caesars assassination had prevented the Republic from becoming a monarchy, it had now provoked a military coup. Or as Cicero put it, the despot may have been removed, but the despotism remained.

Antony now decided to hold an Assembly of the People to try and restore his reputation with the public. His soldiers, who had up until now shown him loyalty berated him over his treatment of Octavian, and Antony was forced to publicly denounce the assassins. It was around this time that Cicero, who saw himself as the saviour of the Republic, said that Octavian was somebody to be “flattered, used, and pushed aside”. This statement was to prove fatal for the orator later on as Octavian and Antony struggled for supremacy in Rome.

Meanwhile, sensing an oncoming fight, Octavian was discreetly gathering the support of the Macedonian-based legions, which was technically treason. By inducing state troops to abandon the legitimate army, and fight for him (if it proved necessary) a private individual, was playing a dangerous game. He also set about recruiting thousands of Caesars retired veterans, on the promise of large sums of money once any fighting was over.

Also, one of the assassins, Brutus, was still causing problems, as he still commanded several hostile legions that squared up to Antony’s brother Gaius, the consul of Dyrrachium in present-day Albania. Gaius fled to Italy, leaving Brutus in charge of Dyrrachium, just across the Adriatic sea, which was too close to the Italian mainland to be comfortable for Octavian, should Brutus wish to make a grab for Rome itself.

It was now Antony made a grave mistake. Whilst gathering support, he addressed troops at Brundisium, and lost his temper when the gathered troops harangued him publicly for not executing Caesars assassins. He gathered up several of the ringleaders and executed them, and warned the others not to desert to Octavian. Storming off the rostrum he bellowed ‘You’ll learn to obey my orders!’

The result was two entire legions, the Martian Legion, named after the God of War and The Fourth Legion abandoned Antony and went over to Octavian. The young man now controlled a private army nearly 10,000 strong.

Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius had taken up arms against Octavian, starting the so-called Perusine War. Octavian’s general and friend Salvidienus Rufus, with Agrippa, surrounded Lucius Antonius’s forces in Perusia. The other Antonian generals, who had no clear orders from Mark Antony, remained out of the struggle, and Lucius Antonius was forced to surrender after a few months’ siege, during the winter of 40 BC. After the end of the Perusian War, Octavian sent Salvidienus to Gaul as a governor, with a large army. There followed several skirmishes and two major battles with Antony (who had now absorbed Lepidus’ men into his own legions), including the long running seige of the town Mutina, which saw Octavian (at first shakily – by his own admission he was no natural-born soldier) prove his worth in the field, far too much political wrangling by the likes of Cicero back in Rome, including him making his ill-judged quote about pushing Octavian aside, and yet more desertions of Antony’s men to Octavian’s camp.

A stalemate now ensued, with neither side strong enough to beat the other, and both men treading warily around the senate as not to be declared an enemy of the state. Octavians courtship of the Roman people continued alongside Antony’s growing fascination with Egypt and its queen.

An election was forced later that year in Rome that saw Octavian voted in as a consul, with twelve vultures being seen on voting day above the city, the same amount that Romulus allegedly saw the day he founded the city in his own name. Octavian took that as a good omen, and immediately held a special court to try, in their absence, Caesar’s assassins. All were found guilty. One of the judges who sat on the tribunal had the courage (or the lack of common sense) to disagree with the verdict, and was later killed for it.

There was now a lengthy period of relative calm between the opposing factions. At nineteen, Octavian had become Romes youngest consul; his private army, now eleven legions strong was legitimised by the senate, and was well-paid and loyal. It had been, so far, an incredible rise to power, but the real test of his character was only just beginning.

”At the age of nineteen, on my own initiative and at my own expense, I raised an army by means of which I restored liberty to the Republic, which had been oppressed by the tyranny of a faction…”

The Emperor Augustus

Leave a comment