This article was posted on June 18, 2021 by Ron Current stillcurrent.blog/2021/06/18/the-roman-forum-searching-for-caesar I thought it was really interesting read and it is something that isn’t common knowledge for a lot of people. Peter Stothard’s book The Last Assassin details a part of the story behind Current’s article, it’s a great read and was published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in October 2020.

After his assassination, Caesar’s body was taken to his home on the Via Sacra in the Forum, the Domus Publica. This was the official residence of the Pontifex Maximus, the title Caesar held when he was murdered. The Domus Publica was part of a religious and political complex within the Roman Forum. The other buildings of this complex were the House of the Vestal Virgins, the Temple of Vesta, and the Regia. It was at the Regia, as Pontifex Maximus, that Caesar conducted his official business.

To find the locations of the Domus Publica and the Regia in the Forum, you’ll need to enter by its eastern entrance, at the Arch of Titus. Walk down the slight incline until you reach the Temple of Romulus. Across from this temple, there is an open and ruin-filled field, this is where the Domus Publica had stood, Julius Caesar’s home for almost twenty years. To find the ruins of the Regia, walk just a little further into the Forum. Between the Temple of Antonius and Faustina and the Temple of Vista, you’ll see the small triangle of a stone foundation. This foundation is all that remains of the Regia, Caesar’s office, so to speak.

For Caesar’s funeral, Calpurnia, his wife, and her servants prepared his body following the traditions at the time. In the last century of the Roman Republic, the preferred practice was cremation, not inhumation (burial) or embalming. To the Romans of that time, those practices were considered to be foreign customs. So, following the norm, Caesar wasn’t embalmed; instead, they washed the body and then applied perfumed ointments to it. From accounts of Caesar’s funeral, their preparations didn’t help much to mask the condition of a five-day-old corpse with multiple stab wounds.

Most historians agree that Julius Caesar’s funeral took place on March 20th, 44 BCE, five days after his assassination. Caesar’s body was to be carried in a procession from the Domus Publica to the Campus Martius. At that time, ancient Rome was surrounded by a religious “city limits” called the “Pomerium.” It was forbidden under Roman religious law to cremate or bury a body inside the Pomerium. So outside this boundary, at the Campus Martius and near the Tomb of Julia, they had prepared a pyre for Caesar’s cremation.

Caesar’s body was placed on an ivory couch and covered with a gold and purple cloth. His pallbearers, magistrates and former magistrates, carried his body out of the house feet first. This was due to an ancient superstition that said if the deceased is carried out this way their spirit will not return to haunt them.

Out on the Via Sacra, the procession was led by Piso, Caesar’s father-in-law, followed by the bier bearing Caesar’s body. Calpurnia came next, walking behind the bier. She was followed by the professional mourners, who wailed and cried in grief, both real and practiced. Last were the singers who sang traditional Roman funeral dirges. This must have been quite a spectacle for all the Roman citizens lining the Via Sacra as they watch the procession pass. However, before going to the Campus Martius the procession was to make a stop in the Forum at the Rostra. There, Marc Antony had arranged for a public funeral to honour Caesar.

The Rostra is just a very short walk down the Via Sacra from the Domus Publica. To find the Rostra continue walking west on the Via Sacra to the western side of the large open area on your right. This area was the Forum’s main square. Now, near the Temple of Saturn, and in front of the Arch of Septimius Severus, you’ll see what looks like a 12-foot high brown wall. These are the remains of the Imperial Rostra.

When Caesar’s funeral procession arrived they were greeted by an extremely large crowd that filled the Forum’s entire main square. As the pallbearers carried Caesar’s bier up the rear steps of the Rostra the crowd began wailing and moaning, filling the air with a horrible noise. The Greek historian Appian of Alexandria tells that there was also a large number of armed men, some retired legionaries, who surrounded the Rostra to protect the body of Caesar.

With solemn reverence, the pallbearers placed the bier with Caesar’s body upon the platform of the Rostra. Next to it was a wax torso of Caesar, which mechanically rotated, with 23 cuts depicting where the assassin’s knives had struck. Also, next to the body was displayed the bloody and slashed clothes worn by Caesar on the Ides of March.

One of the first to speak was Marcus Junius Brutus, a ringleader in the assassination. Brutus spoke in defense of what he and his fellow senators had done. He told the crowd that the senate believed that Caesar was becoming too ambitious, and jeopardized the Roman Republic; and because of this, they were justified in killing him.

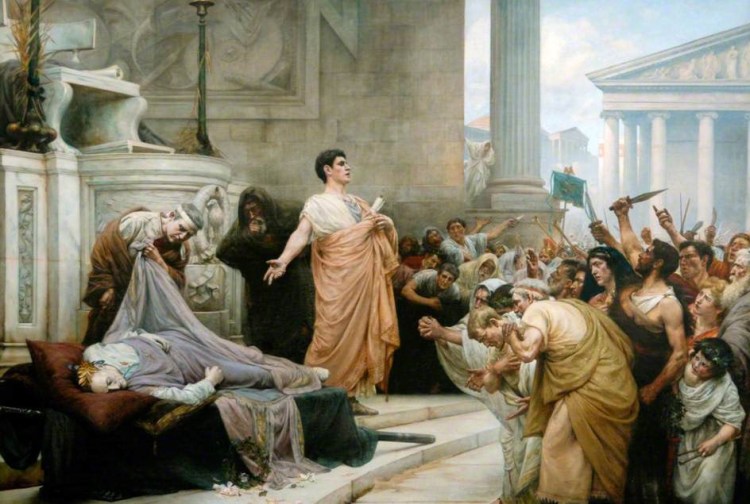

However, the crowd seeing the horror of Caesar’s body, the stab wounds visible, the rotating wax torso, and his blood-soaked clothes kept the crowd from buying into what Brutus had said. But most of all, the assassins had completely misjudged the popularity of Caesar amongst the citizens of Rome. The stage was set, as the mass of mourners were becoming more and more agitated. The powder keg was ready; it just needed someone to light the fuse. Marc Antony, Caesar’s friend, and Consul walked up the steps of the Rostra, taking his place next to Caesar’s body, ready to deliver his funeral oration.

“Friends, Romans, and countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.” These lines by Marc Antony at Caesar’s funeral in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar are perhaps the most recognized and well known in all of Shakespeare’s works. However, what the real Marc Antony said and did was much more dramatic, and more powerful, than what Shakespeare could ever have come up with.

Both historians, Appian and Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, tell what happened when Marc Antony had taken his place on the Rostra. Before he spoke, Antony had a herald read the decree passed by the Senate just before they assassinated Caesar. In this decree the Senate declared Caesar to be divine and with all honour. Antony then had the herald recite the oath that he and all the senators had taken. With this oath, they pledged to guard and protect Caesar from all harm, and that any man, who had taken this oath and failed to protect Caesar, would be cursed forever.

When the herald had finished Antony addressed the crowd, pointing out key points in the decree, where the Senators had referred to Caesar as their leader, benefactor, and the father of his country. Antony also reminded the crowd of the oath he and the senators had taken. He then stretched out his hand toward the temples on Capitoline hill behind him and called out, “Oh Jupiter, god of our ancestors, and you other gods, for my part, I am prepared to defend Caesar according to my oath and the terms of the curse I called down on myself.” Antony went on to say, “But since it is the view of my peers that we have decided what will be for the best, I pray that it will be for the best.” This drew loud cries and curses from the crowd.

Brutus, and the other senators in the crowd, called out their protests to what Antony was saying. Antony answered them, “We must attend to the present instead of the past.” After that, he recited a Roman funeral chant. When finished, Antony took the bloody, ripped clothes that Caesar had worn when murdered, holding them up for all the masses to see; he called out those who had committed this deed as, “villains and bloody murderers.” Marc Antony had turned the tables on the conspirators. With the reading of these decrees and his oration, he had painted those conspirators as traitors, not patriots. What followed, the historians write, was absolute mayhem.

The crowd had heard enough; they went from being mourners to an angry mob; their wailings got louder, their cursing more vengeful. With raised clenched fists they began calling for the perpetrators of this foul deed to pay with their lives. Hearing this, the senators quickly slipped away. But this was only the beginning of what the enraged mob would do.

Rushing the Rostra they pushed aside the guards and seized the bier with Caesar’s body. Led by those carrying the bier the mob swarmed west, up the Via Sacra toward the Capitoline Hill. It’s believed they intended to cremate Caesar there, on Rome’s most sacred ground. But that plan was derailed when the way was blocked by priests.

Turning back, they raced down the Via Sacra to the area in front of the Regia, between the Basilica Aemilia and the Temple of Castor and Pollux. The crowd then raided the surrounding buildings and temples, looking for anything that would burn: benches, tables, chairs, furniture. With these, they built a massive funeral pyre. When they’d finished building the pyre the couch bearing Caesar’s body was placed on top. They then used torches to set it ablaze.

As was the Roman tradition, mourners began tossing personal items such as jewelry, clothing, and military awards onto the fire, adding fuel to the blaze. Historians described the fire as being so large that it soon went out of control, causing damage to several other buildings in the Forum.

When the fire finally consumed Caesar’s body the still enraged mob took up torches and began running through the streets of the city. They planned to burn down the houses of Caesar’s assassins, and hopefully, with them still inside. But by then most of the senators had already retreated to their homes and bolted the doors. Although the mob was able to start a few small fires, their attempts to burn out the murderers failed.

What saved the conspirators and their homes was how the Roman city houses were constructed. They were built without ground floor windows, denying the rioters access to the house. Besides, the building’s exteriors had very little that could burn. But the actions of this angry mob did send a message to the perpetrators; it wasn’t safe to stay in Rome.

When night came, many of the conspirators with their families slipped out of the city unseen. They headed out to the country estates, either their own or those of their families or friends. Others hastily fled Italy to take the governing positions awarded them by Caesar, before they killed him.

The funeral of Julius Caesar was less of a memorial to a great leader, than a referendum on the future of Rome. Brutus and the other conspirators had thought of themselves as liberators and preservers of the Roman Republic, and this is what they presented to the crowd. But Marc Antony used the funeral as a means of channeling the popularity of Caesar for his political gain. In the end, Antony was more persuasive in turning the crowd against the senators.

Caesar’s assassination and funeral set in motion a series of events and civil wars, which ultimately ended the very institution that those senators wanted to preserve, the four-hundred-fifty-year-old Roman Republic, and would eventually help to create the Imperial Roman Empire.

When the sun finally rose on the morning after the funeral, and as his assassins fled Rome, Caesar’s cremation pyre had finally burned itself out. All that was left at the eastern end of the Forum’s main square was a pile of ashes, among which were the blackened bones of the Dictator for Life, Gaius Iulius Caesar.

Leave a comment