The Romans celebrated the New Year as a time of new beginnings and fresh starts, and New Year celebrations in ancient Rome were full of symbolism and held huge significance. Janus, the god who the month of January is named after, was often depicted with one face looking backward and another face looking forward, representing an appraisal of the past and a hopeful expectancy for the future.

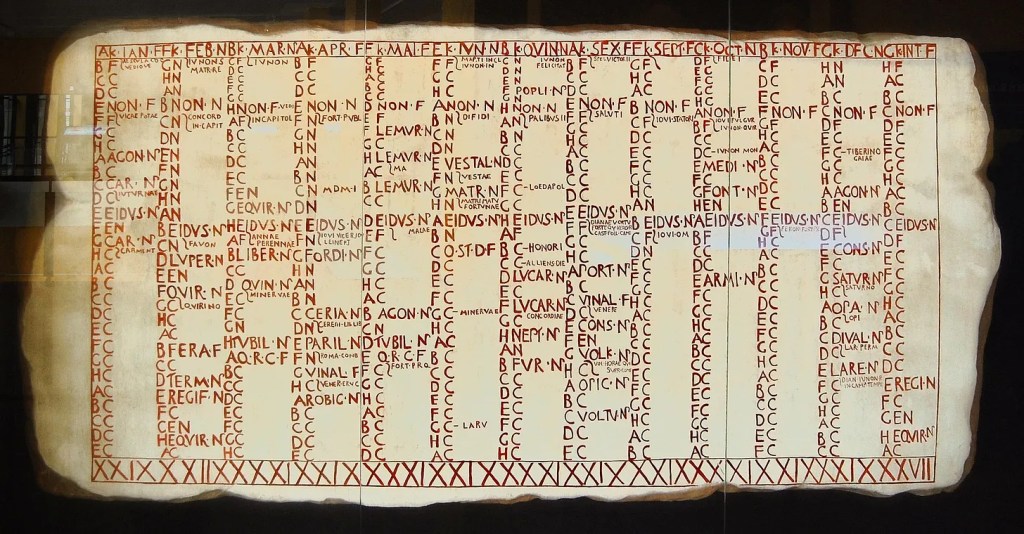

The Romans linked each year to the date of the founding of the city of Rome. So the year 753 BC was marked as year one in the ancient city. In 713 BC their second king Numa Pompilius, introduced two new months, January and February. The new year was still acknowledged, but it began on the 1st March, the month dedicated to the god Mars, in which spring, or the rebirth of nature was celebrated.

Some people believe that the New Year started on 1st January thanks to Julius Caesar, when he introduced the Julian Calendar. Actually, the date had already been modified over a century before by a certain Roman consul, one Quintus Fulvius Nobilior.

In 153 BC, Nobilior led 30,000 legionnaires into Spain, a campaign which was to turn out largely unsuccessful. The Roman army was initially deployed against the town of Segeda, whose inhabitants, the Belli, had been attacking other nearby tribes, and expanding their power base. Nobilior attacked and destroyed Segeda, but the Belli reassembled under a chieftain called Carus, who proceeded to ambush the Roman army in a devastating move compared to the Battle of Lake Trasimene (fought in June 217 BC when a Carthaginian force led by Hannibal ambushed a Roman army commanded by Gaius Flaminius) inflicting heavy losses on them.

Nobilior was given the consulship in 154 BC, however his appointment could not begin until the Ides of March, the day that marked the traditional end of the calendar year. To overcome this, because of the pressing need for immediate military action, the Roman Senate decreed January 1st as the new beginning to that particular civil year, which as time went on gradually became a customary rule across the empire.

When in 153 BC the new year was moved to January 1st, along with Julius Caesar’s calendar reform in much later in 46 BC, this date was officially established as the start of the year. Caesar was elected pontifex maximus in 63 BC, when the position was mainly a religious office, but it slowly became a political as well as religious role as the Empire grew, and the Emperor Augustus made it part of his duties, maintaining the pax deorum or “peace of the gods”. The title still exists today, being used ‘unofficially’ by the Pope.

On a New Year’s Day, the Romans used to work for a few hours, so that idleness wasn’t the first part of the New Year. Later they exchanged the Strenae (good omens) – gifts of dates, dried figs, honey, and branches of laurel, collected in the small roadside woods along the Via Sacra. Gifts were exchanged as Roman society depended on reciprocity, the practice of giving and receiving, deeply rooted as essential for survival. The Latin names for gifts were donum and munus. Donum was a gift given freely, and munus was a gift given in the course of duty. The exchange of such gifts helped form and maintain social bonds throughout society.

People drank wine at social gatherings, and at the last toast they dipped their fingers in the goblet, then touched a wooden statue of Dionysus (the Roman god Bacchus) to bring in good luck.

It was the duty of the Pontifex Maximus to offer the gods gifts such as salt, spelt, cheese and focaccia in order to gain favour for the crops. Also they gave small sacrifices of grain, grapes, cakes, or honey to the Penates that guarded the home. The Penates were the household deities, which were called upon in domestic rituals. When the family ate, they threw a piece on the fire on the hearth for the Penates. Thus the Penates were associated with Vesta, the virgin goddess of the hearth, home, and family in Roman religion. She was rarely depicted in human form, and was more often represented by the fire of her temple in the Roman Forum.

All of this had a purpose – as contractual relationships in society, these gifts were serving everybody, a ”you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” scenario.

The New Year in Rome was greeted very solemnly and cheerfully as laeta dies (a joyful day). The Romans believed that if the first day of the new year was spent happily, so it would continue to be the whole year. People gave a kiss and or a handshake to friends and family, exchanging gifts, believing that a modest gift of a coin or a small parcel of food meant more as the gods truly favoured the poor.

Other gifts given could be white candles which were called Cerei, and small wooden figurines, to dice, wine, tooth picks, sponges, pigs bladders to be used as footballs, cheap books of bad poetry and sheep heads.

State officials offered these gifts to their underlings, students gave to their teachers and the poor gave to their helpers. The emperors graciously accepted gifts from their friends and retinue, and sometimes members of the public, and in return they gave gifts of money and practical help to the poor, and presents to children and the elderly.

Leave a comment