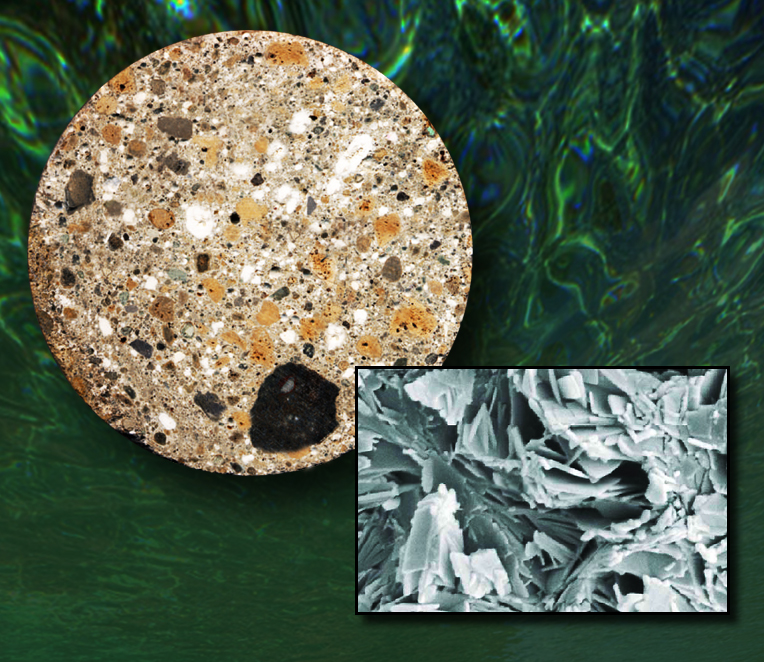

Herod the Great’s Roman-built harbour at Caesarea Maritima, present-day Israel

We’ve known about it for centuries, but now it seeems we are willing to study the properties and chemical mixture of Roman concrete in a little more depth, because it is particularly well suited to marine structures, and could help us out of what is now a global problem. This enduring concrete amazingly hardens and becomes more durable as it is exposed to saltwater. Some researchers now believe that the secrets of this ancient building material could perhaps help us adapt to a world of rising sea levels.

As global temperatures rise, sea ice is melting and causing the oceans to rise at a faster rate than ever before. Exactly how much it will rise is unknown, but there is a strong possibility that rising sea levels will force us to reinforce coastal infrastructure around cities. Venice is already sinking, and currently there’s no way of stopping it.

One of the most direct solutions for a coastal city is to construct a seawall. These structures do not need to hold back the ocean constantly, but rather are built to block the water from the city during high tide and storms that can cause flooding. The Malecón in Havana, Cuba, for example, is a five-mile-long roadway and seawall that guards the city from flood water. Seawalls are used around the world in the United Kingdom, the USA and Australia.

The Romans had the perfect recipe for water-resistant concrete. It was made with volcanic ash found in the region of The Gulf of Naples in Italy, and they called the material opus caementicium, which is made from a hydraulic cement, meaning it can set underwater or in wet conditions. The Romans mixed this cement with volcanic ash which contained a mineral called phillipsite, which when mixed with the concrete, causes aluminous tobermorite crystals to grow inside the concrete when it is exposed to water. These crystals are what makes Roman concrete so durable, because they act like tiny armour plates and keep strengthening the concrete by allowing the material to flex rather than shatter as it bends. It’s not a common finding either, it’s a natural process that’s only been seen before in the Surtsey volcano in Iceland.

Between 22 and 10 BCE the King Herod, with the help of the Romans constructed an underwater concrete foundation for the harbour of the ancient city of Caesarea, in what is now Israel. This marine structure is still intact today, more than two thousand years later. The study of ancient Roman concrete suggests that the material could be recreated using modern technology to build and strengthen existing seawalls around the world.

Pliny the Elder, the famed Roman author, historian, and philosopher, wrote in his Natural History “As soon as it comes into contact with the waves of the sea and is submerged, [it] becomes a single stone mass, impregnable to the waves”.

Because artificially producing aluminous tobermorite crystals requires a large amount of heat and energy simply to synthesize a small amount, to recreate Roman saltwater resistant concrete, it will be the easiest to harvest it from the natural source of heat and energy where it comes from: volcanoes.

The recipe for Roman concrete was described around 30 B.C. by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, an engineer for Octavian, the later Emperor Augustus. They combined the volcanic ash with lime to form mortar. They packed this mortar and rock chunks into wooden molds which were then immersed in seawater. Rather than try to think of a way of keeping the saltwater out, the Romans saw it as a necessary part of the concrete.

Shipping was absolutely the lifeline of political, economic and military stability for the Romans, so constructing harbours that would last was critical. As the Roman Empire declined, shipping declined, so naturally the need for seawater concrete declined. But the original structures were so well constructed that once they were in place, that was it, the job was finished as they needed next to no maintainence.

But researchers are now finding ways to apply the rediscovery of Roman concrete to the development of more earth-friendly and durable modern concrete. They are investigating whether volcanic ash would be a good large-volume substitute in countries without easy access to fly ash, an industrial waste product from the burning of coal that is commonly used to produce modern concrete.

There is not enough fly ash to replace just 50% of the Portland cement being currently used in the world, at present around 17 billion tonnes of the stuff, so the idea should be to find alternative, local materials that will work, including the stuff the Romans used. It could hopefully improve the durability of modern concrete, which within 50 years often shows signs of degradation, particularly in ocean environments.

The manufacturing of Roman concrete also leaves a smaller carbon footprint than does its modern counterpart. The process for creating modern concrete, requires fossil fuels to burn limestone and clays at about 1,450 degrees Celsius. Approximately 7% of annual global carbon dioxide emissions comes from this burning. The production of lime for Roman concrete, however, is much cleaner, requiring temperatures much lower than that required for modern concrete.

Saudi Arabia has “mountains of volcanic ash” to quote Paulo Monteiro, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, that could potentially be used in concrete. His analysis shows the lime reacting with aluminum-rich pozzolan ash and seawater forming the highly stable tobermorite crystals, insuring great strength and incredible longevity.

“For us, pozzolan is important for its practical applications,” says Monteiro. “It could replace 40 percent of the world’s demand for Portland cement. And there are sources of pozzolan all over the world. Saudi Arabia doesn’t have any fly ash, but it has mountains of pozzolan.”

Looking from a wider perspective, the building of aqueducts were another source of engineering the Romans excelled at, many of them still standing and able to transport water, at a push admittedly, today. These aqueducts were almost completely watertight due to the extremely precise engineering techniques used. The stones used in the construction were cut and fitted together to create a watertight seal without the need for mortar. Then the Romans used the technique of pouring concrete (opus caementicium) into the gaps between the stones, further increasing the ability of the structure to prevent water ingress or egress. This method allowed the aqueducts to transport water over long distances without hardly any loss of water.

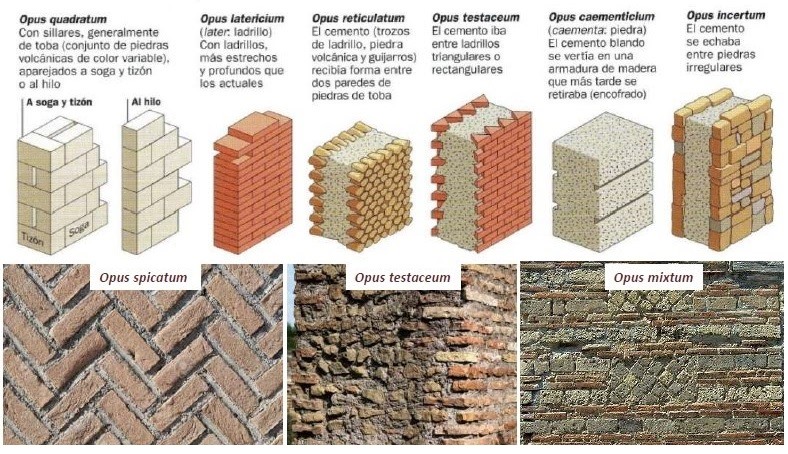

The chart below shows the different types of brickwork and cement that the Romans used in their building works.

Translation of the captions;

Opus quadratum = With ashlars (hewn or squared stone) generally made of tuff (a set of volcanic stones of variable colour) rigged with rope and brand or thread.

Opus latericium = With bricks, narrower and deeper than regular ones.

Opus reticulatum = The cement (pieces of brick, volcanic stone and pebbles) is shaped between two walls of tuff stones.

Opus testaceum = The cement is poured between triangular or rectangular bricks.

Opus caementiclum = Soft white cement is poured into a wooden framework that is later removed (formwork).

Opus incertum = The cement is poured between irregular stones

In addition to their practical function, Roman harbours and aqueducts were considered remarkable feats of engineering and architectural achievement, becoming symbols of power, showing the world the capability of the Roman Empire, be it in military matters or trade.

For a short look at Roman seawater defences click here

For a downloadable article entitled The History and Technology of Roman Concrete Engineering in the Sea click here

References: Roman Seawater Concrete Holds the Secret to Cutting Carbon Emissions by Paul Preuss, 2013

Leave a comment