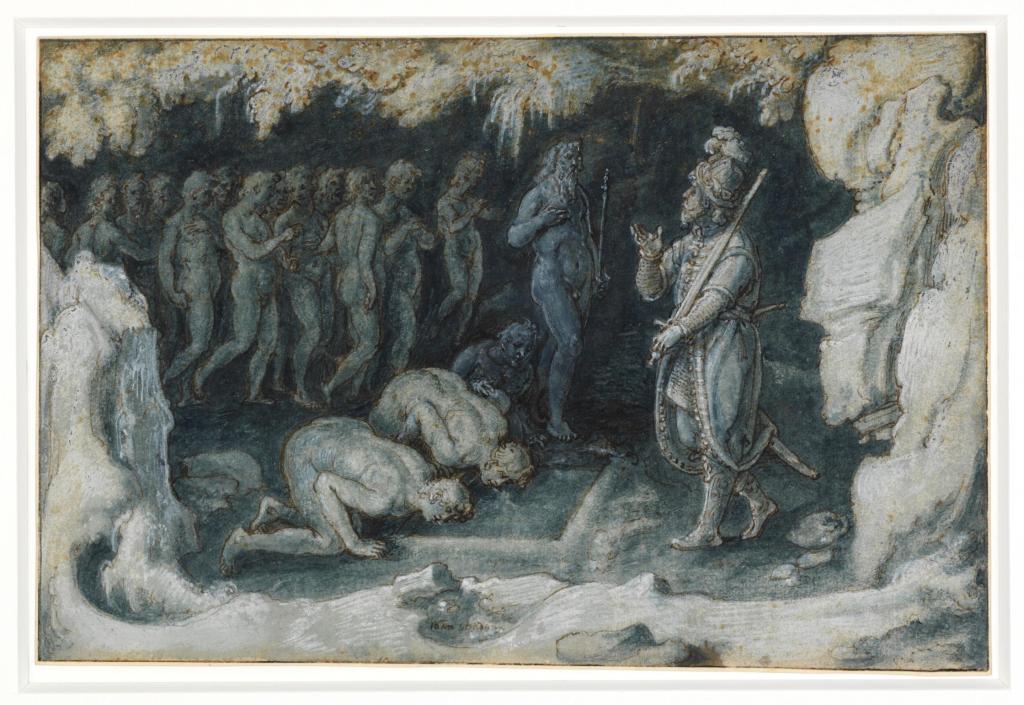

Cerberus who guarded Hades

To tell the story of the beginning of the universe, the time of Chaos (literally ‘Yawning Gap’ – the infinite space between heaven and earth), and the gods that followed it in Greek mythology, is no straightforward affair. There are a multitude of characters, all with different roles to play, but the original and most complete source of the myths and their origin is the Theogony of Hesiod, that was first written down in around 700 BC, to describe the ascendancy of Zeus, and the rise of the other deities.

In Hades, the souls of the dead resided alongside a series of deities, better known as the Chthonic Gods. The most prominent of these gods were Hades, Persephone, Demeter, and Hecate, along with the Furies, all playing an important role in the underworld of Greek mythology. The word chthonic comes from the Greek ‘khthon’, which means ‘earth’ or ‘soil’ and literally translates to ‘under the earth’.

So, a very simplified version of the fantastical, mythological events that formed the ancient world would be as follows:

Back near the beginning of time, Cronos was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans, the descendants of Gaia, mother Earth (who emerged from Chaos, and from whom all gods and goddesses are descended from), and Caelus (the Sky or Heaven), supreme ruler of the the Universe. Cronos had overthrown his father Caelus, after castrating him with a scythe, enabling him to become the undisputed ruler of the world. He then took Rhea, his sister, to be his wife, and with her had six children, Hades, Poseidon, Zeus, Demeter, Hera, and Hestia. Cronos, after learning his children would one day overthrow him, ate all his offspring except Zeus, who Rhea hid in a cave on the island of Crete, giving instead Cronos a stone wrapped in swaddling, which he promptly ate, believing it to be his son.

Saturn Devouring His Son by Francisco Goya 1823

Upon reaching adulthood, Zeus overthrew his father and made him disgorge his siblings. His kingdom was then divided among them, and the underworld fell by lot to the first-born son, Hades, who although less than satisfied with his realm, reluctantly accepted it and became the Greek god of the underworld, where he governed over the over the infernal powers and the dead. He ruled with his queen, and niece, the young Persephone whom he had abducted as a child with the help of his brother Zeus, into what was often called “the house of Hades,” or simply Hades. He was aided by the terrifying three headed guard-dog Cerberus, who ensured no one could leave, and kept the living from entering the underworld, although as we shall see, some brave souls made the journey.

Just speaking his name was considered unwise, so he was often referred to as Plouton, the wealthy one, because it was supposed that all the riches of the earth could be found in his kingdom. Another name given to him was Zeus Katachthonios: ‘Zeus of the Underworld.’ Hades was always depicted as stern and pitiless, he ruled his realm with a grip of iron, unmoved by prayer or sentiment, just as death is itself…

In Greek mythology there were three divisions to the underworld, Elysium, Tartarus and Asphodel. The Elysium Fields was where heroes and great warriors went. If you took up arms and died a hero, your reward was eternal residence in the Elysium Fields. You would remain there to live a blessed and happy afterlife. Very often those who went to Elysium did so not because of their heroic behaviour, but because of their status and family connections with the gods. These fields were, according to Homer, located on the western edge of the Earth by the stream of Okeanos. By Hesiod’s time (c. 800 BC) , the Fields would be known as the Fortunate Isles or the Isles of the Blessed, and was home to those judged as exceptionally pure.

Meanwhile, the wicked were damned to Tartarus, the infernal region of the ancient world, described as a dark place, a deep abyss that is surrounded by the river of fire and walls, where the gods locked up for all eternity their enemies. As Zeus thunders ”…I shall take and hurl him into murky Tartarus, far, far away, where is the deepest gulf beneath the earth, the gates whereof are of iron and the threshold of bronze, as far beneath Hades as heaven is above earth: then shall ye know how far the mightiest am I of all gods” (Homer, Illiad, Book 8), and where they would the be punished by the minions of Hades, the Furies or sometimes Erinyes, the gods of vengeance who had sprung forth from Uranus’ blood when he was castrated, at least according to the Theogony.

Once the evil that had resided in the individual had been destroyed, the soul, called a shade, went to the same place as with those who had lived a mediocre life. Here in the Fields of Asphodel, human spirits were turned to shadows and spent eternity wandering in a field of asphodel flowers. But the Greeks themselves knew that Asphodel was no paradise. The passages below comes from Homer’s The Odyssey when Odysseus ventures to the underworld, an instance where a mortal went to the underworld and returned to the living, a mythological journey known as a katabasis:

“The dead approach him in swarms, unable to speak unless animated by the blood of the animals he slays. Without blood they are witless, without activity, without pleasure and without future” The Odyssey, Book XI

Drinking the blood of slain animals enables the shades to speak a language that would otherwise be unintelligible to human beings, and as Odysseus himself says…

”From this multitude of the souls, as they fluttered to and fro from the trench, there came an eerie clamour. Panic drained the blood from my cheeks.’

The Asphodel Meadows is the name inspired by the plant Asphodelus, an unattractive plant, chosen by the Greeks because of its ghostly grey colour which is appropriate to the shadowy atmosphere of the underworld. Others explain the name of the land as ‘field of ashes’ basing it on the Greek words sphodelos or spodelos, ‘ashes’, or ’embers’, again because of the colour of the ashes of a dead fire.

After their deaths in the Trojan War, the legendary Greek warrior Achilles made a deal with Hades that his childhood friend Patroclus got to go to Elysium, instead of Asphodel, and Achilles had to enter the House of Hades in his place. Here the famed warrior confronts his former comrade, Odysseus: ‘How did you dare to come below to Hades’ realm, where the dead live on as mindless disembodied ghosts?’ Later, he says, ‘I would rather work the soil as a serf on hire to some landless impoverished peasant than be King of all these lifeless dead.’ Hades was obviously no place for a great warrior.

Greek mythology depicts the land of the dead as having a dark atmosphere, gloomy, frightening, dark and generally unpleasant for heroes to endure. Homer writes ”Looking after him [Agamemnon] as he went, Odysseus saw that beyond the dusky grove lay a vast meadow, covered with flowering asphodel, where troops of souls were roaming in a pale light like misty moonshine”. It seems that Hades was the place where human souls were indiscriminately thrown together, and led a ghostly semi-existence.

Odysseus’ mother, Anticleia, describes the underworld as a ‘murky realm’ and ‘no easy place for the living keys to find.’ Odysseus describes his love for his mother, which compels him to embrace her: ‘Three times, in my eagerness to clasp her to me, I started forward. Three times, like as shadow or a dream, she slipped through my hands and left me pierced by an even sharper pain.’ In the underworld, it is impossible for the dead to hold their loved ones – they have lost the muscle and sinews required to hold their bones to their flesh.

Orpheus ventured into Hades to rescue his wife Eurydice, who had died of a snake bite. He so charmed Hades with his singing that he was allowed to leave with her, provided he would not gaze on her face until they were free of the Underworld. Orpheus unfortunately looked back at his wife as she followed him at the last moment and she was lost to him forever.

All souls had to drink from the river Lethe before entering these fields, thus losing their identities. It is possible that this somewhat negative outlook on the afterlife for those who make little impact in this world, was perhaps passed down the generations in Greek society to encourage militarism.

The dead who had been given funeral rites were guided by the God Hermes, in his form known as psychopompos, a soul guide, to Charon the ferryman of the Greek underworld, for their journey to Asphodel, which was across the rivers Acheron and Styx, both of which separated the worlds of the living and the dead. Charon was the son of Erebus, the god of the dark regions and the personification of darkness, and Nyx, the female personification of night but also a huge figure in her own right, feared even by Zeus, the king of the gods, as told in Homer’s Iliad.

According to the Suda (a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient world, attributed to the author Soudas), the ancient Greeks placed a honeycake with the dead in order for them to give it to Cerberus, to placate him. A coin was placed in the mouth of the corpse for Charon’s payment, a custom that still resonates today in some parts of the world, usually with coins being placed over the closed eyes of the dead. Charon was represented as a miserable and ugly old man, eventually coming to be regarded as the image of the underworld. As such he survives as Charontas, the angel of death in modern Greek folklore.

There were many entrances to the Underworld that were named in ancient sources, a cleft in the ground on Sicily, used by Hades himself, a cave entrance at Taenarum, used by both Orpheus and Heracles, Aeneas the founder of the Roman race, used a cave upon Lake Avernus in Italy, and Odysseus entered the underworld via Lake Acheron, in the Epirus region of northwest Greece, and the Lernaean Hydra, (the killing of which became infamous as one of Heracles twelve labours), guarded another entrance on the eastern coast of the Peloponnese.

In modern-day Israel is Caesarea Philippi, an ancient Roman city now uninhabited. During the years 323 to 31 BC, this city was originally called Panias, after the greek god Pan. In 2 B.C., one of Herod the Great’s sons, Philip, renamed it Caesarea in honor of the emperor Augustus. The cave just north of the city was known as the gate to the underworld, with one of Hades’ sobriquets being the ‘gate fastener’.

Hades itself did not acknowledge the human concept of time, it just existed for evermore. The dead were aware of both the past and the future, and in many stories of the Greek heroes, the protagonists were helped by the shades prophesying, giving them instructions and telling hitherto unknown truths, in order to aid them in their quest. This was called nekuia, a rite by which shades were summoned and questioned about the future. These fables aside, the Greeks in general had a belief in an afterlife, believing that death was not the complete end, and accepting it for what it was, but saw the afterlife as largely a meaningless existence.

The Greek poet Sappho ties it up neatly in her short verse on the reality of death:

Translated by Chris Childers

Leave a reply to Myth – A world of the imagination Cancel reply