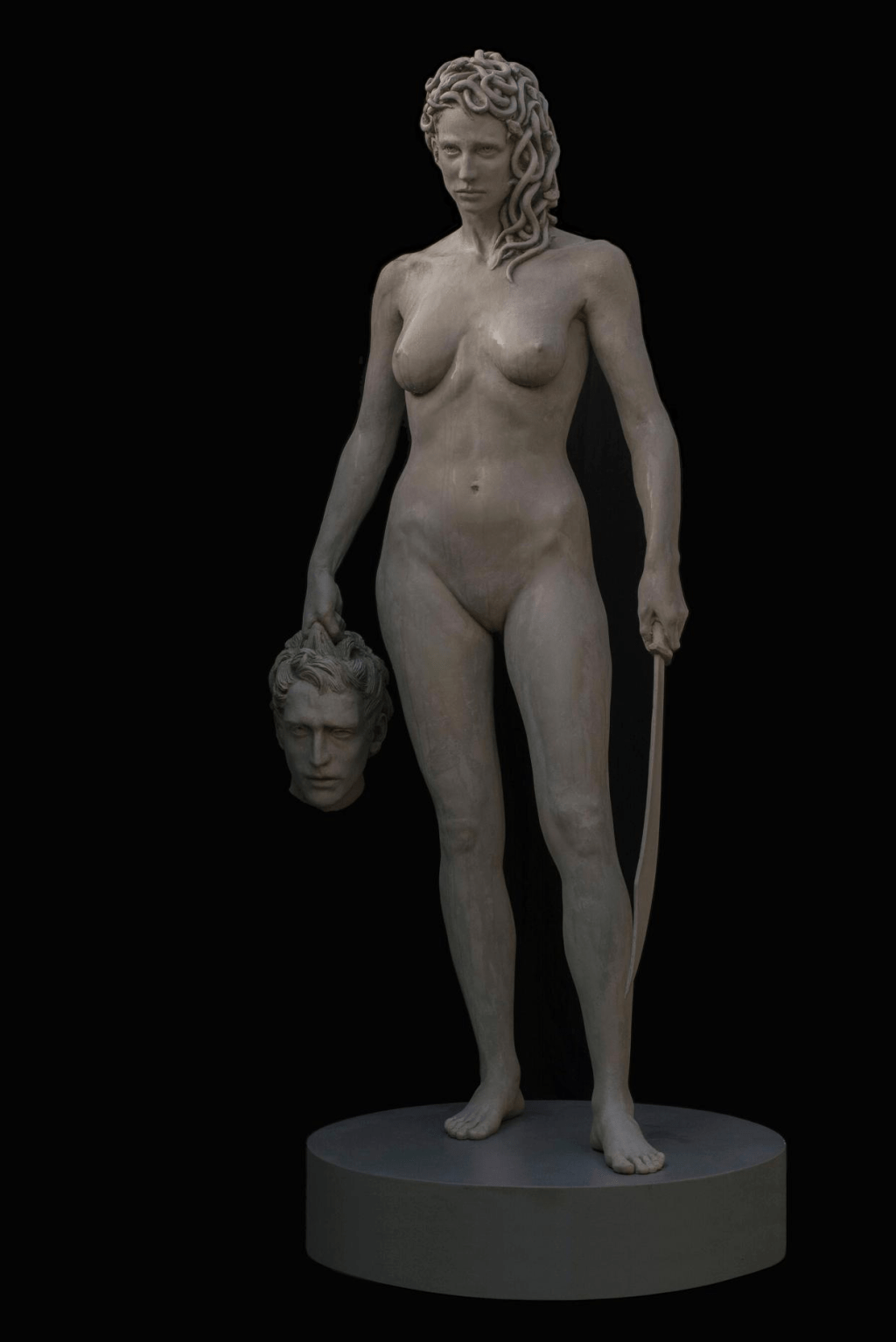

Luciano Garbati, Medusa holding the head of Persues, 2008

To some, the Greek myth of Medusa is a nightmarish tale, one of madness, a demonic monster with snakes for hair and a glance that has a petrifying power, while others such as the Roman poet Ovid, have interpreted her as a wronged woman, a symbol of revenge and dangerous femininity, but to all, Medusa’s story is probably the best known of the Greek myths.

In ancient Rome, Publius Ovidius Naso rewrote the Greek myth, portraying events in a very different light. In his Metamorphoses, he tells of Medusa being raped by Poseidon in the temple of Athena, and the goddess, with her anger at her shrine being defiled like this, focused her rage onto Medusa, turning her into the monster we know today. Is this really fair? What woman would punish another for being raped?

Thanks to an Italian-Argentinian sculptor, the myth has been revived recently and Medusa has become an icon for the Me-Too movement. The artist Luciano Garbati cast a seven foot tall statue in 2008 purely as a work of art, but in 2020 it was sited in the Manhattan Collect Pond Park for six months, right in front of the New York Criminal Court, where Harvey Weinstein was convicted of rape. It has become a symbol for female rage. Garbati says that he wanted to make up for Medusa’s unjust characterisation as the villain of the story, and his work gained widespread attention on social media in the wake of the #MeToo movement—as well as some criticism.

Some have lamented the fact that the statue was made by a man, others saying the statue is too sexy, Medusa is after all shown naked with a resolute look on her face, she is not snarling with hatred or contempt. As a piece of art, the figure is banal. She is too easy on the eye — there is nothing striking or remotely challenging about her, more femme fatale than ferocious monster. Some others have asked if a statue of a naked woman created by a male artist is really expressing the power of the feminist driven #MeToo movement, or why Medusa is not holding the head of her alledged rapist Poseidon, instead of Perseus.

But all Greek sources prior to Ovid’s version don’t have an element of rape to them, and Poseidon’s relationship to Medusa is assumed by many to be consensual, so she was not, in the original myth, a sexual assault victim of Poseidon. Hesiod is the first author to write about this, and we should keep in mind that Athena is not mentioned in his story. Hesiod describes the encounter between them as them “laying together in a soft flowery meadow”, with her being beheaded by Perseus at the end of the myth, for abandoning her vow of chastity. This torrid love affair would produce two children, sons called Pegasus and Chrysaor, who both sprang from her severed neck when Persues beheaded her.

It’s important to contextualise this story, as Ovid was a writer who had problems with authority, ending up exiled from Rome for some serious misbehaviour with the emperors daughter. His mythologic poetry is generally understood as a form of political back-stabbing against authority figures, who were represented by the gods. That’s why in a lot of Ovid’s retellings of pre-existing myths (such as this one) the Gods are depicted as being cruel towards mortals.

Ovid’s work has been massively influential throughout history, and today we only take into account his version of the story as “Greek” mythology. The poet was very popular in Rome before, and during, his exile so he felt he had the right to elaborate on an already old story, and his version, now old to us, has passed down the millennia to become the accepted one. The earliest Greek versions of the myth don’t feature Medusa’s rape at all, she willingly engaged in an affair with the sea god. Ovid is the one who invents the rape element, originally Athena was simply furious that Medusa had abandoned the vow of chasity she had taken, hence her terrible revenge.

Garbati’s work was originally intended as just a reversal of Cellini’s 16th century sculpture, made to look sexy for the modern times we live in, but has become much more, due to it’s placement opposite the law courts. Feminism was not what Garbati had in mind when he cast the statue, but he did try to reimagine the myth through the victims narrative.

As the journalist Karen Attiah said in October 2020, ”one strong criticism has emerged: Should a pretty, naked woman killing a man really serve as a symbol for women who have survived male abuse?” The #MeToo founder Tarana Burke has criticised the statue. On Instagram, she said that the “movement is not about retribution or revenge and it’s certainly not about violence. It is about Healing and Action.”

Leave a comment