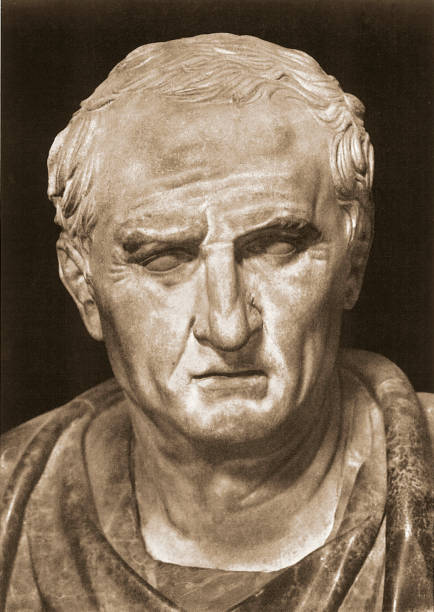

Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106 – 43 BC

After building a career as a skillful barrister in the law courts, and putting down the Cataline insurrection, Cicero had not only become a shrewd politican, but one of the best orators and lawyers the Roman world had ever seen, many of his works surviving to the present day. He achieved every high office available to him, quaestor, aedile, praetor, and consul on his first attempt, and at the earliest age at which he was allowed to run. He was lauded by the Senate and celebrated as the ‘Father of the Nation’, and is nowadays widely regarded as the most of flexible and versatile minds of ancient Rome.

He was born on January 3, 106 BC, in Arpinum (modern-day Arpino), a town some 100 kilometres south east of Rome, his fellow Arpinians receiving Roman citizenship in 188 BC, along with other Italian communities, making Cicero’s future as a Roman statesman possible. Although Cicero was not “Roman” in the traditional sense, and certainly not a wealthy or elite one, his family were gentry, they had money, and although relatively modest, his political enemies in Rome would not allow him to forget this: he was a ‘novus homo‘, a new man, one without an elite family lineage, and as such was never truly accepted – he was very self-conscious of this throughout his entire life.

Choosing a career in law, he prepared by studying jurisprudence (the philosophy and theory of law), rhetoric, and philosophy, travelling to Greece where he studied philosophy with Antiochus of Ascalon, the ‘Old Academic’. In Asia Minor, he met the best orators and continued to study with them. Cicero then journeyed to Rhodes to meet with Apollonius Molon, a famous rhetorician who had previously taught Cicero while on a visit to Rome. Molon helped Cicero hone his craft, including exercises such as running through sand, to cope with the demands of speaking in public. He also studied under Philo of Larissa, the head of the Academy that was founded by Plato in Athens in about 400 BC, when he arrived in Rome. Cicero absorbed Plato’s philosophy, respecting his immense imagination, but ultimately rejecting much of his work, along with the too austere (certainly for him!) stoicism. Stoicism maintained a popular appeal in Roman society, and a man who practised the philosophy, named Diodotus lived with Cicero in his house until his death, maintaining an attitude the great stoic teachers would have been proud of, when despite going blind he continued to teach his students.

Titus Pomponius Atticus (110 BC – 32 BC) was a Roman banker, and patron of letters, and is largely famous for becoming Cicero’s closest friend and adviser. “You are a second brother to me, an ‘alter ego’ to whom I can tell everything,” Cicero wrote in one of his letters to him. Atticus was from a wealthy Roman family of the aristocratic equestrian class, and schooled along with Cicero, proved himself an excllent student, studying Epicurean philosophy, and becoming adept in business. He faithfully provided Cicero with 250,000 sesterces when the statesman had to quickly flee Rome in 49 BC. Atticus had inherited money, and he successfully invested it in real estate, enhancing his wealth. He used this wealth to support his love of writing, and letters, publishing many of his friends works. His appraisals of the Greek authors Plato and Demosthenes, were noted for their accuracy by the Romans. He was also a friend and business partner of Crassus, a member of the First Triumvirate, also known as the richest man in Rome, from whom he borrowed 3.5 million sesterces to buy a house on the Palatine.

Cicero married twice, the first marriage to Terentia in 79 BC lasted some 30 years, and although a marriage of convenience, it was harmonius and they got along well, Terentia giving birth to a daughter they named Tullia, who became the apple of her fathers eye. Terentia was a strong willed woman who did not share her husbands intellectual pursuits, but believed in him, and gave him large amounts of money to further his political aims. In around 50 BC Cicero told friends he believed Terentia had betrayed him, but it is unknown in what way, and they seperated, divorcing in 46 BC. A year later he married a young girl, Publilia, but after Tullia suddenly died, the marriage quickly collapsed with Cicero blaming his young wife of being unsympathetic over the death, and being jealous of her. Removing himself from society to complete solitude in his villa at Astura, Cicero grieved terribly in the months after his daughters death, writing to Atticus “I plunge into the dense wild wood early in the day and stay there until evening”. Among others, both Caesar and Brutus sent him letters of sympathy.

He wrote a book on overcoming grief, titled Consolatio, which was highly regarded in antiquity, but is now lost. A few fragments have survived, among them the sad lament “I have always fought against Fortune, and beaten her. Even in exile I played the man. But now I yield, and throw up my hand.”

Cicero had a son Marcus, who he wished would become a philosopher like him, but Marcus wanted a military career, joining the army of Pompey in 49 BC, and after Pompey’s defeat at Pharsalus 48 BC he was pardoned by Caesar. After his father’s murder, Marcus joined the army of the Liberatores, as the assassins of Caesar called themselves, but was later pardoned by Augustus. Augustus aided Marcus’s career, and he became an augur, was nominated consul in 30 BC, and was later made a proconsul of Syria and the province of Asia.

Marcus Tullius Tiro, who died in his hundreth year in 4 BC, was a slave, then a freedman, of Cicero from whom he received his nomen and praenomen. He is often mentioned in Cicero’s letters, and the two had a genuine friendship. After Cicero’s death Tiro published many of his letters and speeches, and a biography which is believed was later used as a main source in the historical works of both Plutarch, and Tacitus. He is also thought to have invented an early form of shorthand, some of which is still in use today. When, in 51 BC Tiro fell seriously ill, Cicero was distraught, and his letters show the strength of their friendship, with Cicero regularly writing to check on Tiro’s health.

As a politican Cicero’s vision for the Republic was not simply keeping the status quo, nor a desire to revitalise the collapse of the republican system. Cicero wanted to see Rome ruled by a selfless nobility of successful men ruling by consensus in the Senate. Because of his country background Cicero had a broader outlook, less absorbed by self-interest than the wealthy patricians of Rome. He believed that only “some sort of free state” would bring stability and justice. Cicero did not expect any major reform of the selfish, ambition ridden government, yet he yearned for a return to the ‘golden’ era of the republic; but this vision had some flaws, as that age probably never truly existed. He was constantly disappointed as Pompey, Crassus and Caesar at first joined forces, then fell apart, and then watched the country descend into civil war. After Caesar had taken power in Rome, many plots to remove him were allegedly organised until 44 BC, when he was killed by a group led by his friend (and son of his mistress Servilia) Marcus Junius Brutus, an ancestor of the Lucius Junius Brutus who had expelled the last of Rome’s kings centuries before. Although Cicero had not been one of the conspirators, he had sympathised with it and was disappointed in the Liberatores, as Caesar’s assassination backfired and failed to reinstate the Republic. But Cicero lacked the political power, or military skill, to bring his idea to life. And so, the situation in Rome rolled on to its inevitable bloody conclusion.

Caesars’ murder gave Cicero the hoped-for opportunity to finally see his dream come to fruition. Caesar was dead, the Senate became once again important, and Cicero wanted to be at the forefront of its rejuvination, doubtless so he could achieve even greater fame (Cicero was always known as a somewhat vain man) as ‘father of the nation’. Consequently he started to give a series of speeches that became known as the Philippics (named after the speeches the Greek orator Demosthenes made to rouse the Athenians to fight Philip of Macedon in the 4th century BC, speeches that set the standard in Roman times for a political attack), that called for the Senate to aid Octavian, Caesars successor, in defeating Marc Antony in the civil war.

… I could not, on the one hand, endure to live under a monarchy or a tyranny, since under such a government I cannot live rightly as a free citizen nor speak my mind safely

– Cicero, on his beloved Republic, according to Cassius Dio’s Roman History 45.18

Cicero felt that Antony should also have been killed, sensing him as a threat to the survival of his beloved republic. In the Philippics, Cicero attempted to rally the Senate, but Octavian was forced to try and bargain some form of peace with Antony, who demanded Ciceros proscription if talks were to go any further. After two days of arguing, Antony got his way, and Octavian, somewhat reluctantly, agreed to add Ciceros name to the list, and Antony had him tracked down to Caieta (now Gaeta), despite Cicero being viewed with sympathy by a large segment of the public, and executed. His head and hands were taken to Rome where they were nailed to the speakers podium (the rostrum) as a warning to others. Allegedly, Antony’s wife Fulvia pulled out Cicero’s tongue, and jabbed it repeatedly with a hairpin in a final act of revenge against his power of speech.

Cicero’s son, Marcus, during his time as consul in 30 BC, partially avenged his father’s death when he announced to the Senate Mark Antony’s defeat at the Battle of Actium by Octavian (later Augustus). The Senate subsequently voted to prohibit all future descendants of the Antony family from using the name Marcus.

Years later, Augustus found his grandson reading a book written by Cicero. The boy tried to hide it, scared of what his grandfather would say. The Emperor took the book from him, read a part of it, and then handed it back, and said ” A learned man, dear child, a learned man who loved his country”.

Leave a comment