Woman with Stylus, an ancient Roman fresco unearthed in Pompeii

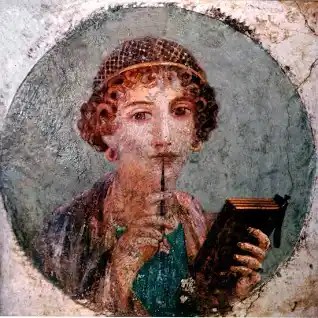

In the late 19th Century a series of excavations at an ancient rubbish dump in the city of Oxyrhynchus, around 100 miles south of Cairo, were undertaken that found some valuable papyrus scrolls that included a sizeable amount of long-lost poetry by the Greek poet Sappho. She was well known in the ancient world, with Plato calling her ‘the tenth Muse’, and others knowing her as the ‘female Homer’. Her work speaks largely of unrequited love and longing between two women, and is the reason we talk of such relationships between women as lesbian, because she came from the Greek island of Lesbos. She is thought to have written around 10,000 lines of poetry, although unfortunately today, we know of only about 650. She is best known for her lyric poetry, written to be accompanied by music. Exiled to Sicily in around 600 BC because of a political scandal involving her family some time between 604 and 595, she continued to work until around 570 BC. According to legend, she killed herself by leaping from the Leucadian cliffs due to her unrequited love for the ferryman Phaon.

The next is an article written by Charlotte Higgins, the Chief Arts Writer of the Guardian newspaper, and was originally published in January 2014

Sappho: two previously unknown poems indubitably hers, says scholar

A University of Oxford papyrologist is convinced poems preserved on ancient papyrus are by the seventh-century lyricist of Lesbos, Sappho.

But now, two hitherto unknown works by the seventh-century lyricist of Lesbos have been discovered. One is a substantially complete work about her brothers; another, an extremely fragmentary piece apparently about unrequited love.

Sappho is one of the most elusive and mysterious – as well as best-loved – of ancient Greek poets. Only one of her poems, out of a reputed total of nine volumes’ worth, survives absolutely intact. Otherwise, she is known by fragments and shards of lines – and still adored for her delicate outpourings of love, longing and desire.

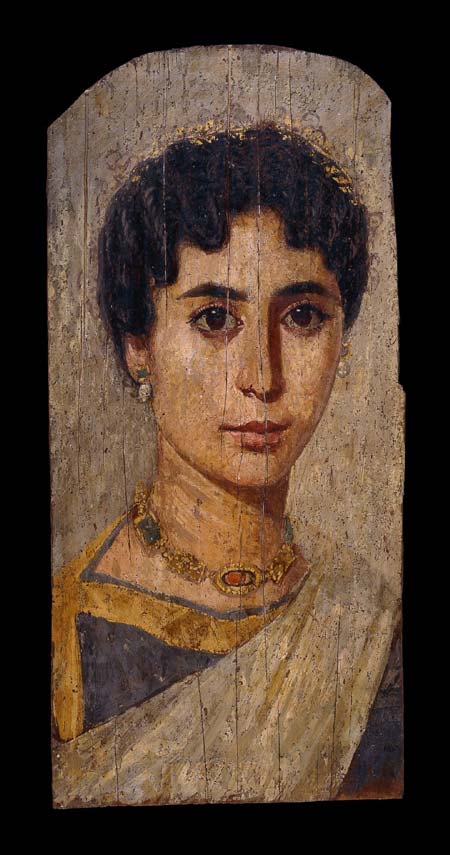

The poems came to light when an anonymous private collector in London showed a piece of papyrus fragment to Dr Dirk Obbink, a papyrologist at Oxford University.

According to Obbink, in an article to be published this spring, the poems, preserved on what is probably third-century AD papyrus, are “indubitably” by Sappho.

Not only do elements of the longer poem link up with fragments already known to be by her, but the metre and dialect in which the poems are written point to Sappho.

The clincher is a reference to her brother, Charaxos – whose very existence has long been doubted, since he is mentioned nowhere in previously discovered fragments of Sappho.

In this poem – though it is not the precise one that Herodotus mentions – the writer addresses her audience, seeming to berate them for taking Charaxos’s return by ship from a trading trip for granted.

However, Herodotus, the fifth-century BC historian, named the brother when describing a poem by Sappho that recounts the tale of a love affair between Charaxos and a slave in Egypt.

Pray to Hera, says the narrator, “so that Charaxos may return here, with his ship intact; for the rest let us leave it all to the gods, for often calm quickly follows a great storm”.

According to Tim Whitmarsh, a professor of ancient literature at Oxford University, the poem could be read as a play on Homer’s Odyssey, and the idea of Penelope waiting patiently at home for the return of Odysseus. Sappho frequently reworked Homeric themes in her poems.

The poem goes on to say that those whom Zeus chooses to save from great storms are truly blessed and “lucky without compare”. The poem ends with the hope that another brother, Larichos, might become a man – “freeing us from much anxiety”.

Sappho, who was born in about 630BC, is known for her lyric verse of longing, often directed at women and girls – the bittersweet feeling of love, impossible-to-fulfil desire and the sensation of jealousy when you see the object of your obsession across the room, talking intimately with someone else.

She was admired in antiquity for her delicate, passionate verses. The only evidence for her biography comes from within her poems – and the naming of her brothers, Charaxos and Larichos, adds substantially to a sketchy knowledge of the poet’s life.

Sappho’s poems, which were lost from the manuscript tradition and were not collated and copied by medieval monks as were so many surviving ancient texts, have been preserved by two main means: either through quotation by other authors (often as examples of particular syntactical points by ancient grammarians) or through the discovery of fragments written on ancient papyrus. There is hope yet for more poems to come to light, preserved in the Egyptian sands.

Obbink’s article, with a transcription of the original poems, is to be published in the journal Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik.

For articles on the authenticity of the discovery of Sappho’s poems in Egypt click here and here

[…]

But you always chatter that Charaxus is coming,

His ship laden with cargo. That much, I reckon, only Zeus

Knows, and all the gods; but you, you should not

Think these thoughts,

Just send me along, and command me

To offer many prayers to Queen Hera

That Charaxus should arrive here, with

His ship intact,

And find us safe. For the rest,

Let us turn it all over to higher powers;

For periods of calm quickly follow after

Great squalls.

They whose fortune the king of Olympus wishes

Now to turn from trouble

to [ … ] are blessed

and lucky beyond compare.

As for us, if Larichus should [ … ] his head

And at some point become a man,

Then from full many a despair

Would we be swiftly freed.

Translated by Tim Whitmarsh, professor of ancient literature at Oxford University, and originally published in The Guardian newspaper on Thursday 30th January 2014

Translated by Chris Childers

Leave a comment